"The scientists," Nicole tells me as we settle in for the SOWG meeting, "are all in a tizzy about not receiving any data."

"A tizzy?" I repeat, rolling it around. "A tizzy, a tizzy ... they're all in a heap." She giggles.

I never find out what provoked the tizzy. We seem to have all of our drive data, at least, and we're going to use it; we're starting our partial circumnavigation of Home Plate. Our egress drive went perfectly, and Friday's meeting resolved that we'd traverse the thing clockwise. (This was rather a surprise: counterclockwise was the strongly preferred direction among the oddsmakers, as that path offered much better science. Unfortunately for the oddsmakers -- and for science -- it also offered much worse solar energy, and recent orbital imagery revealed that a troublesome valley blocked our way. Moreover, there was reason to think that the appealing stratigraphy of the counterclockwise route would be obscured by talus. So clockwise won in a squeaker.)

We'd hoped to hug the rim all the way, but the area nearest Home Plate is relatively smooth. Yeah ... a little too smooth. Visually, it's somewhere between the kind of hard-packed, gravelly stuff our rover eats for breakfast, and the kind of shifty, loose, Arad-like stuff we get hopelessly bogged down in. Expert opinion shrugs, so we decide to exercise the better part of valor. I mean to say, we drive around it. This takes us farther from Home Plate, and thus lengthens the drive, but if it keeps us from getting mired in the mud (pray forgive the poetic license), the detour will be well worth it.

At the end of our blind drive, as we're rounding the corner of Home Plate, we have a choice: up onto a rocky, west-tilted ridge, or across the smooth stuff. I aim Spirit right across the smooth stuff -- with a slip check after just a couple of meters, and periodic checks beyond. If it's good for driving, we'll cruise along nicely on autonav. If not, we won't go far into it before the slip check stops us, so we won't have far to back out.

[Next post: sol 768, March 1.]

2011-02-27

2011-02-24

Spirit Sol 763

The IDD sequencing is already done (despite a moment where they were discussing entirely changing it), so we're able to focus entirely on the drive. And since I picked out the waypoints yesterday, this isn't too bad. We're going back down more or less the way we came up, so if we hit our waypoints closely enough -- which visodom will help us do -- we know just about exactly what Spirit will experience on the way. It's a steep climb down, with tilts hovering just over 20 degrees, and only a narrow safe channel. To one side, the terrain slopes away even more sharply; to the other, a jumble of exposed bedrock would perhaps take our tilt over the 25-degree limit. "This is one of those drives where you wish you could be there to see it happen," Squyres marvels.

Fortunately, John and I have gotten darn good at this. We mustn't become overconfident, but our success in nailing long approaches, threading needles, and so on, has given us confidence that this will go pretty well.

For no readily apparent reason, the day ends up taking longer than you'd think it would; we're here something like 11 hours. Saina feels bad about the outcome, but Steve gives her a pep talk.

"Look at what we're doin'!" he says. "Complicated IDD work, then a really cool drive, then PANCAM observations of the Phobos transit. Now, imagine going back to sol 40 and saying you're gonna plan all of those in one day. Really, think about it!"

He's right, as usual. Like the rovers themselves, this team has come a long way. And if we can make it to McCool Hill in time, the best is yet to come.

[Next post: sol 766, February 27.]

Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech. A frame from the Phobos transit imaging. Hey, we're not all about the driving! The astronomy is pretty darn amazing, too.

Fortunately, John and I have gotten darn good at this. We mustn't become overconfident, but our success in nailing long approaches, threading needles, and so on, has given us confidence that this will go pretty well.

For no readily apparent reason, the day ends up taking longer than you'd think it would; we're here something like 11 hours. Saina feels bad about the outcome, but Steve gives her a pep talk.

"Look at what we're doin'!" he says. "Complicated IDD work, then a really cool drive, then PANCAM observations of the Phobos transit. Now, imagine going back to sol 40 and saying you're gonna plan all of those in one day. Really, think about it!"

He's right, as usual. Like the rovers themselves, this team has come a long way. And if we can make it to McCool Hill in time, the best is yet to come.

[Next post: sol 766, February 27.]

Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech. A frame from the Phobos transit imaging. Hey, we're not all about the driving! The astronomy is pretty darn amazing, too.

2011-02-23

Spirit Sol 762

Today's work is trivial -- an IDD tool change. I'm glad of that, because it gives us a chance to get ahead on tomorrow's work, which will be decidedly less trivial. Tomorrow we're driving across Home Plate -- or possibly back down, so we can start driving around it -- and that'll be after some relatively complex IDD work. Experience teaches us that that's more than we can comfortably do in one day, so we might as well get as much as possible done now.

The problem is that we don't know where we're driving. Well, our basic options are to go across Home Plate, or to go down so that we can go around it one way or the other. So in the couple of hours we have before the end-of-sol meeting, I sketch out the waypoints for each path.

Meanwhile, other members of the team are pointing out that we won't do much driving for the next few days. Monday was a holiday, and we're still in restricted sols, so we can drive on either Thursday or Friday but not both. Or, of course, we could delay the drive until the weekend -- the point is that between Thursday and Sunday, we can do only one drive. We'll have an IDD sol, a drive sol, and two sols of remote sensing and/or recharging. Since the latter are, from a planning perspective, basically free, and we don't have a pass Monday, Saina proposes we do something we've never done before: a four-sol plan, where we come in tomorrow (Thursday) to plan Friday through Sunday all in one day. (This seems like a lot to me, but when she slyly adduces that some people think it's impossible to do a four-sol plan, I'm suddenly enthusiastic. It's like the four-minute mile of rover planning.) If we succeed, that would also mean we'd have Friday off: we'd plan all four sols tomorrow -- Thursday. If we fail, we could just drop the last sol out of the plan and come in Friday to do that one.

Squyres tells her he's for it, too: "Home Plate is the most interesting and exciting science target Spirit's seen so far. I don't want to end up simplifying or cutting science in order to do this. As long as you and I agree we fall back by cutting sols and not science, I'm up for that. It's a deal! Sounds like fun! Let's do it!"

The end-of-sol meeting is an uncommonly interesting one. The topic is where to go from Home Plate, and how to get there. Squyres leads off with a presentation showing Emily and Jake's analysis of our driving situation. We were supposed to leave Home Plate by sol 760 and spend roughly 25 sols driving to our winter home. Curiously, if we delay our exit until sol 780, we get more drive sols in the 25 sols following (thanks to restricted sols and interference from MRO in the earlier period), though the 780 start leaves no time or power for science. "If we leave at 780, there's no stopping even for dinosaur bones," is how he puts it.

There are three big contenders for our winter home:

So McCool Hill wins. But the next question is how to get there -- across Home Plate, down and clockwise, or down and counterclockwise. That's one for me, and I tell them how I see it.

"Any of our three paths to McCool could be blocked. We could drive all the way across Home Plate, only to find there's no way down the other side. From orbital and Husband Hill imagery, we can't prove that we can get around Home Plate, either to the clockwise or counterclockwise directions, without running into a cul-de-sac and needing to come back. Therefore, despite your sol-780 scheme, we need margin: we need to get moving now, and keep moving.

"Of the three paths, I favor crossing Home Plate. Any of the paths could be blocked later, but backing down off of Home Plate will take a sol, maybe two, where we don't make any real progress toward our goal. My next choice would be the clockwise path, since that's better for energy reasons -- we'll have a more easterly tilt. Counterclockwise is my last choice."

Guess which way the science team wants to go? No prize for the right answer. The counterclockwise path will offer significantly better geology. The west side of Home Plate -- the side the counterclockwise path will take us along -- is apparently a much taller face, with more stratigraphy exposed. So Steve punts, asking if we can consider the question Friday, after we've had a chance to do more analysis of the power differences between the clockwise and counterclockwise paths. (The top of Home Plate doesn't appear to offer us anything of comparable interest to either of those paths, so it's out of the running in his mind. Naturally, I've already picked out the waypoints for our first drive along the top. Sigh.)

Well, this gives us enough direction to get ahead on tomorrow's sequencing. We know we're going downhill, so I go ahead and pick out the waypoints for that drive. Plus, they sketch out the IDD work they'll be asking for tomorrow, and Ashley gets that sequence in the bag. Our Monday pass comes back on the table after all, so they drop the four-sol plan -- tomorrow we'll do a three-sol plan, planning Thursday through Sunday and coming in Monday as normal. But we'd have been ready for it. It would have been awesome.

The problem is that we don't know where we're driving. Well, our basic options are to go across Home Plate, or to go down so that we can go around it one way or the other. So in the couple of hours we have before the end-of-sol meeting, I sketch out the waypoints for each path.

Meanwhile, other members of the team are pointing out that we won't do much driving for the next few days. Monday was a holiday, and we're still in restricted sols, so we can drive on either Thursday or Friday but not both. Or, of course, we could delay the drive until the weekend -- the point is that between Thursday and Sunday, we can do only one drive. We'll have an IDD sol, a drive sol, and two sols of remote sensing and/or recharging. Since the latter are, from a planning perspective, basically free, and we don't have a pass Monday, Saina proposes we do something we've never done before: a four-sol plan, where we come in tomorrow (Thursday) to plan Friday through Sunday all in one day. (This seems like a lot to me, but when she slyly adduces that some people think it's impossible to do a four-sol plan, I'm suddenly enthusiastic. It's like the four-minute mile of rover planning.) If we succeed, that would also mean we'd have Friday off: we'd plan all four sols tomorrow -- Thursday. If we fail, we could just drop the last sol out of the plan and come in Friday to do that one.

Squyres tells her he's for it, too: "Home Plate is the most interesting and exciting science target Spirit's seen so far. I don't want to end up simplifying or cutting science in order to do this. As long as you and I agree we fall back by cutting sols and not science, I'm up for that. It's a deal! Sounds like fun! Let's do it!"

The end-of-sol meeting is an uncommonly interesting one. The topic is where to go from Home Plate, and how to get there. Squyres leads off with a presentation showing Emily and Jake's analysis of our driving situation. We were supposed to leave Home Plate by sol 760 and spend roughly 25 sols driving to our winter home. Curiously, if we delay our exit until sol 780, we get more drive sols in the 25 sols following (thanks to restricted sols and interference from MRO in the earlier period), though the 780 start leaves no time or power for science. "If we leave at 780, there's no stopping even for dinosaur bones," is how he puts it.

There are three big contenders for our winter home:

- A flatiron slope to the southwest. This would offer good northern exposure, but the path to it may be blocked, it's far away, and it doesn't look too scientifically interesting.

- Von Braun Hill, just south of Home Plate. Its base is readily accessible, but the interesting stuff, a huge caprock, is likely out of reach because the slopes leading to it are too steep. What's left is insufficiently scientifically interesting for a 200-sol winter.

- The north flank of McCool Hill, our original plan. This turns out to have at least three huge bedrock exposures (named Korolev, Oberth, and Faget, all after rocketry pioneers). It's farther away than Von Braun, but offers us good tilts and great science.

So McCool Hill wins. But the next question is how to get there -- across Home Plate, down and clockwise, or down and counterclockwise. That's one for me, and I tell them how I see it.

"Any of our three paths to McCool could be blocked. We could drive all the way across Home Plate, only to find there's no way down the other side. From orbital and Husband Hill imagery, we can't prove that we can get around Home Plate, either to the clockwise or counterclockwise directions, without running into a cul-de-sac and needing to come back. Therefore, despite your sol-780 scheme, we need margin: we need to get moving now, and keep moving.

"Of the three paths, I favor crossing Home Plate. Any of the paths could be blocked later, but backing down off of Home Plate will take a sol, maybe two, where we don't make any real progress toward our goal. My next choice would be the clockwise path, since that's better for energy reasons -- we'll have a more easterly tilt. Counterclockwise is my last choice."

Guess which way the science team wants to go? No prize for the right answer. The counterclockwise path will offer significantly better geology. The west side of Home Plate -- the side the counterclockwise path will take us along -- is apparently a much taller face, with more stratigraphy exposed. So Steve punts, asking if we can consider the question Friday, after we've had a chance to do more analysis of the power differences between the clockwise and counterclockwise paths. (The top of Home Plate doesn't appear to offer us anything of comparable interest to either of those paths, so it's out of the running in his mind. Naturally, I've already picked out the waypoints for our first drive along the top. Sigh.)

Well, this gives us enough direction to get ahead on tomorrow's sequencing. We know we're going downhill, so I go ahead and pick out the waypoints for that drive. Plus, they sketch out the IDD work they'll be asking for tomorrow, and Ashley gets that sequence in the bag. Our Monday pass comes back on the table after all, so they drop the four-sol plan -- tomorrow we'll do a three-sol plan, planning Thursday through Sunday and coming in Monday as normal. But we'd have been ready for it. It would have been awesome.

2011-02-18

Spirit Sol 757

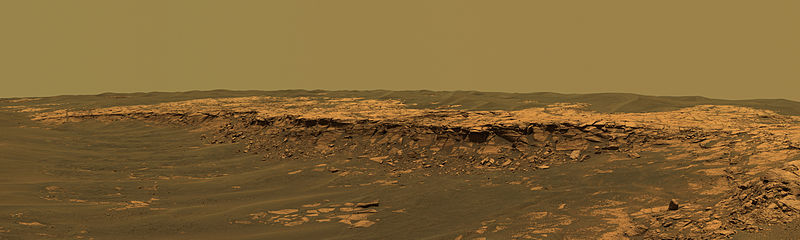

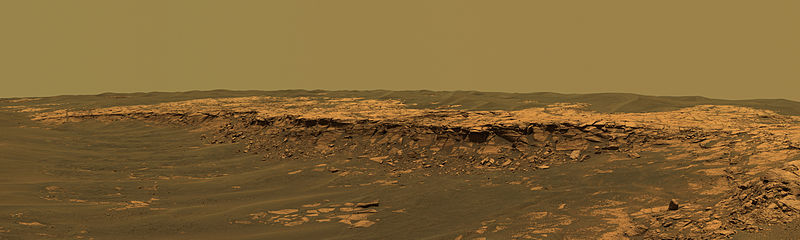

So we're up on Home Plate. It could hardly have gone better. Autonav refused to drive the final 1.5m, but it wouldn't have made any real difference; we're perched right on the rim, with a splendid view of the interior of Home Plate.

Including, not too surprisingly, some terrific rocks. There's a bunch of stratigraphic layered material, light-toned rocks (don't get me started), a layered rock immediately behind us in the RHAZ. There's even what looks like a "lava bomb," a rock that starts off as a glob of lava spit out by a volcano; it freezes back into a roughly spherical or football-shaped rock in the air, before it can even hit -- like the way they used to cast lead shot.

The scientists are doing their kids-in-a-candy-store act. I never get tired of it. But Justin decides he's going to put a bit of a damper on things.

"Are we still leaving by sol 760?" he asks pointedly.

Oded's answer is equivocal, something to the effect that he hasn't heard anything different from Steve yet, but without completely rejecting the possibility of staying longer.

He moves on, resuming talking excitedly with the other scientists about which rocks we should choose, but a few minutes later, Justin interrupts again. "Hey, Home Plate's a big place," Justin says. "Why don't we drive across it and see what we see there?"

This is something I love about Justin. As much as I dig the science team, there's a part of me that knows we need to get on the damn road, for the rover's health and safety. Justin manages to express that part of myself, better than I could -- and since he's doing it, I don't have to, which makes it even better.

I don't think his message really gets across (maybe I should have spoken up after all), but they do manage to focus long enough to pick a destination. They picked the big broad shelf of layered material. It'll be an easy drive, looping in a big arc, then turning and zooming straight to our final position. Once again, we're doing an approach of over 10m. We've been doing a lot of these lately, and nailing them one after another, on a vehicle that wasn't designed for more than a 2m approach.

I love this rover.

And that's a reason the subject Saina brings up later in the day is one of my least favorites, a memento mori. But she raises it in a humorous way. For some reason, they're talking about the last piece of free ice cream, which has languished in one of the freezers all this time. You can see the idea hit her, her eyes widening. "I think when the rovers die, we should have a ceremony where we bury the last piece of the free ice cream!" she exclaims. "Or maybe, we all take a bite, and then we bury the stick or whatever."

Time and chance happeneth to all rovers. When they go, I think that will be a good way to say goodbye.

Many years from now, of course. When I'm an old, old man.

[Next post: sol 762, February 23.]

Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech. A rear HAZCAM view looking up over the top of Home Plate.

Including, not too surprisingly, some terrific rocks. There's a bunch of stratigraphic layered material, light-toned rocks (don't get me started), a layered rock immediately behind us in the RHAZ. There's even what looks like a "lava bomb," a rock that starts off as a glob of lava spit out by a volcano; it freezes back into a roughly spherical or football-shaped rock in the air, before it can even hit -- like the way they used to cast lead shot.

The scientists are doing their kids-in-a-candy-store act. I never get tired of it. But Justin decides he's going to put a bit of a damper on things.

"Are we still leaving by sol 760?" he asks pointedly.

Oded's answer is equivocal, something to the effect that he hasn't heard anything different from Steve yet, but without completely rejecting the possibility of staying longer.

He moves on, resuming talking excitedly with the other scientists about which rocks we should choose, but a few minutes later, Justin interrupts again. "Hey, Home Plate's a big place," Justin says. "Why don't we drive across it and see what we see there?"

This is something I love about Justin. As much as I dig the science team, there's a part of me that knows we need to get on the damn road, for the rover's health and safety. Justin manages to express that part of myself, better than I could -- and since he's doing it, I don't have to, which makes it even better.

I don't think his message really gets across (maybe I should have spoken up after all), but they do manage to focus long enough to pick a destination. They picked the big broad shelf of layered material. It'll be an easy drive, looping in a big arc, then turning and zooming straight to our final position. Once again, we're doing an approach of over 10m. We've been doing a lot of these lately, and nailing them one after another, on a vehicle that wasn't designed for more than a 2m approach.

I love this rover.

And that's a reason the subject Saina brings up later in the day is one of my least favorites, a memento mori. But she raises it in a humorous way. For some reason, they're talking about the last piece of free ice cream, which has languished in one of the freezers all this time. You can see the idea hit her, her eyes widening. "I think when the rovers die, we should have a ceremony where we bury the last piece of the free ice cream!" she exclaims. "Or maybe, we all take a bite, and then we bury the stick or whatever."

Time and chance happeneth to all rovers. When they go, I think that will be a good way to say goodbye.

Many years from now, of course. When I'm an old, old man.

[Next post: sol 762, February 23.]

Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech. A rear HAZCAM view looking up over the top of Home Plate.

2011-02-16

Spirit Sol 755

The plan for today is to back away from Posey and drive up onto the rim of Home Plate. If everything breaks our way, we'll be able to see over it tomorrow, and we can decide whether to drive across the thing or around it. I'd been hoping all the way to Home Plate that it would turn out to look like a salt flat, and we could just zoom across it -- an easy 100m day. But we've had a couple of glimpses over the rim already, and it looks like it's pretty gnarly up there. So going around might be better.

Terry and I separately roughed out a drive path, basically following a route that John spotted when we first drove up here. And since Ashley hasn't been getting much practice as RP-1, I offer her the big chair.

I have a small regret about this decision. On the schedule, Antonio's supposed to be shadowing today, and he gets less coaching and instruction this way. Well, I'll try to remember to give him some extra opportunities next time I work with him. He turns out to be very useful as an analyst, though; we find a couple of rocks whose size we can't evaluate from our current position, and he goes through more than ten sols of prior imagery until he finds a view from which we can prove they're safe. That probably saved us an hour of work right there, and might have even salvaged the drive itself.

Ashley, for her part, does well with the sequencing. We underestimate how long it's going to take, though, and we aren't really ready at the walkthrough. We catch a lot of errors -- so many that we basically have to go back and walk through it again. But I feel pretty good about the end result.

The drive uses visodom virtually all the way to the top. Visodom is especially necessary for the first leg, where we need to get onto a very narrow path leading to the rim. To our left, the terrain slopes away much more steeply; to our right is a rugged outcrop. But in between is a straight, relatively smooth path that was practically made for our rover, it seems. The tilt gets pretty bad up there, though, maybe bad enough to stop us early. We'll see when we get the data.

For the very last meter and a half, part of our view is blocked by an 11cm rock -- not big enough to be scared of, but big enough to obscure the terrain behind it from our current vantage point. So for that part, we turn on autonav, and turn off allowing autonav to drive backward -- something we haven't done for a long time on this vehicle, if ever -- because we don't want it going back down the slope.

The drive distance is relatively short, but the sequence itself is a pretty complex one -- just one of those that need painstaking attention to detail, all the way through. I hope we didn't miss anything, but I don't have a bad feeling about it.

Maybe I should have a bad feeling about that. But I don't.

[Next post: sol 757, February 18.]

Terry and I separately roughed out a drive path, basically following a route that John spotted when we first drove up here. And since Ashley hasn't been getting much practice as RP-1, I offer her the big chair.

I have a small regret about this decision. On the schedule, Antonio's supposed to be shadowing today, and he gets less coaching and instruction this way. Well, I'll try to remember to give him some extra opportunities next time I work with him. He turns out to be very useful as an analyst, though; we find a couple of rocks whose size we can't evaluate from our current position, and he goes through more than ten sols of prior imagery until he finds a view from which we can prove they're safe. That probably saved us an hour of work right there, and might have even salvaged the drive itself.

Ashley, for her part, does well with the sequencing. We underestimate how long it's going to take, though, and we aren't really ready at the walkthrough. We catch a lot of errors -- so many that we basically have to go back and walk through it again. But I feel pretty good about the end result.

The drive uses visodom virtually all the way to the top. Visodom is especially necessary for the first leg, where we need to get onto a very narrow path leading to the rim. To our left, the terrain slopes away much more steeply; to our right is a rugged outcrop. But in between is a straight, relatively smooth path that was practically made for our rover, it seems. The tilt gets pretty bad up there, though, maybe bad enough to stop us early. We'll see when we get the data.

For the very last meter and a half, part of our view is blocked by an 11cm rock -- not big enough to be scared of, but big enough to obscure the terrain behind it from our current vantage point. So for that part, we turn on autonav, and turn off allowing autonav to drive backward -- something we haven't done for a long time on this vehicle, if ever -- because we don't want it going back down the slope.

The drive distance is relatively short, but the sequence itself is a pretty complex one -- just one of those that need painstaking attention to detail, all the way through. I hope we didn't miss anything, but I don't have a bad feeling about it.

Maybe I should have a bad feeling about that. But I don't.

[Next post: sol 757, February 18.]

2011-02-14

Spirit Sol 753

"Why are we at this rock?" Brenda Franklin asks as the SOWG is about to start. "It's not that interesting."

Ashley, who was here for all the craziness of the drive to it, just laughs. "It had better be interesting, after all that!" she says.

The drive went damn near perfectly, I'm happy (not to mention somewhat astonished) to say. In a perfect world, we'd maybe have been a few cm closer and a few cm farther to the left, but compared to how things might have gone, I'm definitely not complaining. Everything we wanted to reach is reachable, there's no rock under the wheel -- Paolo's judgment about nudging us to the right was spot on -- and, as a bonus, we're at a slightly lower tilt than we expected. We can RAT to our hearts' content.

And that's what we're doing, along with other IDD work. As we're in restricted sols, we're planning two sols of IDD work today. The first and more complex sol, with an MI mosaic, RAT placement, and other stuff, is the first one; Chris takes that. Terry's shadowing me today, and I sit with him and coach him through building the less complex IDD sequence for the second sol.

This rock -- which, by the way, has been renamed from "Rock A" to "Posey" -- is probably the last rock we'll investigate in detail here at Home Plate, or anyway at this part of Home Plate. After this, we're going to try to climb up onto the rim, take a peek over it, and then decide if we want to cross it on the way to McCool Hill.

Indeed, there's even some discussion about bagging McCool Hill and just wintering at Home Plate. I hear Larry Soderblom discussing this on the telecon as I work with Terry. "It's maybe not the best use of the rovers," he says. "But we could spend some time crawling along the east side" -- which would help aim the solar panels at the sun -- "and there are good geology questions here, ones that our payload is well suited to answer."

They want to bring Squyres into the discussion, but he's on a plane, or is about to be. So I won't hear the end of that discussion. But I'll find out, I suppose, over the next few weeks.

[Next post: sol 755, February 16.]

Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech. Astonishingly, we made it.

Ashley, who was here for all the craziness of the drive to it, just laughs. "It had better be interesting, after all that!" she says.

The drive went damn near perfectly, I'm happy (not to mention somewhat astonished) to say. In a perfect world, we'd maybe have been a few cm closer and a few cm farther to the left, but compared to how things might have gone, I'm definitely not complaining. Everything we wanted to reach is reachable, there's no rock under the wheel -- Paolo's judgment about nudging us to the right was spot on -- and, as a bonus, we're at a slightly lower tilt than we expected. We can RAT to our hearts' content.

And that's what we're doing, along with other IDD work. As we're in restricted sols, we're planning two sols of IDD work today. The first and more complex sol, with an MI mosaic, RAT placement, and other stuff, is the first one; Chris takes that. Terry's shadowing me today, and I sit with him and coach him through building the less complex IDD sequence for the second sol.

This rock -- which, by the way, has been renamed from "Rock A" to "Posey" -- is probably the last rock we'll investigate in detail here at Home Plate, or anyway at this part of Home Plate. After this, we're going to try to climb up onto the rim, take a peek over it, and then decide if we want to cross it on the way to McCool Hill.

Indeed, there's even some discussion about bagging McCool Hill and just wintering at Home Plate. I hear Larry Soderblom discussing this on the telecon as I work with Terry. "It's maybe not the best use of the rovers," he says. "But we could spend some time crawling along the east side" -- which would help aim the solar panels at the sun -- "and there are good geology questions here, ones that our payload is well suited to answer."

They want to bring Squyres into the discussion, but he's on a plane, or is about to be. So I won't hear the end of that discussion. But I'll find out, I suppose, over the next few weeks.

[Next post: sol 755, February 16.]

Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech. Astonishingly, we made it.

2011-02-11

Spirit Sol 750

Today was brutal. There's just no other way to put it. Brutal.

The science team has identified four rocks in the vicinity that they'd like us to drive to -- A, B, C, and D. Rocks C and D are definitely out; they'll take multiple sols to get to, and one constraint on the solution is that we strongly prefer something we can get to in one sol. Rocks A and B are about equally easy (or difficult) to get to, but A has a patch of sandy material around it, which B doesn't. So at yesterday's pre-plan meeting, I tentatively identified Rock B as the best candidate.

Last night, I took a more careful look, and started falling out of love with that idea. Another constraint on our solution is that we want to be able to RAT-brush our chosen rock, so that we can get a clean APXS measurement on it, and the RATtable face of Rock B is aimed somewhat away from the best path to it. To get to that face, we'd have to clamber up onto the rock pile beside it, which would simultaneously raise our tilt and reduce the stability of our footing. So that's bad all around.

I send out email about that, and the science team weighs the options at the SOWG meeting. What it comes down to is that Rock A is more eroded, so that there will be less layering for the MI. While Rock B offers better MI-ability, the uncertainty about being able to RAT it tilts the choice in the other direction. So Rock A it is.

Before we drive there, we've got some IDD work to finish up at our present location. And it looks like it's going to be hairy; the scientists are still dithering about exactly what they want, and that never turns out well. I turn to Paolo, RP-2 today and still in training to be a full rover driver. "Paolo, which one do you want?" I ask him. "The drive or the IDD?"

"I'm more comfortable with the drive," he says.

"Great!" I answer. "You get the IDD!"

"I knew that was going to happen," he laughs.

Today's going to be tough for him, I can see that. But at some point he's going to have to get his trial by fire, and it might as well be today.

So Paolo and Terry (who's shadowing him) work on the IDD sequence while I put the drive together. The drive to Rock A turns out to be not so terribly complex; we're basically just backing downhill past it, turning, and crawling back up a bit to put it right in the IDD work volume. As always, the devil's in the details, but all in all it goes quite well.

That is, until the TUL tells me there's another constraint on the drive. We've got to be at a heading of 120 degrees for comm. This is significantly different from the "natural" heading we'd otherwise end up at, about 80. It requires a completely different approach, and that means I've got to scrap almost all the work I've done -- I had already finished -- and start over.

A false start or two later, and I've got the new approach roughed out. We'll back somewhat farther downhill, curving until we're straight downslope from Rock A, then turn to about 120 degrees and climb back up to it. This is going to suck. It'll take longer, it means we're trying to drive up a steep slope through sandy material (with the attendant risk of getting bogged down and possibly even picking up a potato), and we've got less time to study it now.

We don't even notice until the walkthrough that the new approach leaves us with the left front wheel up on a 16cm rock. And there's just not much we can do about it, either. As Paolo points out, our choice of destination constrains us in X and Y, and our heading is dictated to us by comm. Therefore, the rover's final position and orientation are more or less completely determined by the constraints on the solution, and if there's a rock under the wheel as a result, then there's a rock under the wheel. We're able to shift the rover's position by a few cm, but will it be enough? Doubtful.

All in all, I'm quite frustrated by this outcome. We were trying so hard to find a scientifically desirable rock we could reach in one sol; our sols here are already limited, and Monday we enter restricted sols, which means we'll blow two more sols if this doesn't work. And I don't have any confidence that it will work: I think we'll come in Monday and have to reposition. This just sucks.

Worse yet, switching to Rock B (or C or D) at this point wouldn't help: C and D are more than one sol away no matter what we do, and B still has the same problem of higher tilt plus unsure footing, especially if we know we'll have to come at it with a 120-degree heading. So we wouldn't have options to fall back on even if the team weren't too tired and stressed out to attack them.

With all this going on, it's no wonder we discover -- after delivering -- an error in Paolo's IDD sequence. One part of the sequence is a column of MI stacks marching up the rock face. The rock face curves away from us slightly, and Paolo's sequence doesn't account for that. As a result, we're not quite touching the rock at the top end of the mosaic, and the resulting MI images might be out of focus (though the lower images in the stack will probably be just fine). Maybe I shouldn't bother with this, but I have to do my job. I smile sweetly at our TUL.

"Hey, Colette," I say as casually as I can. "What would you say if I told you there was a problem in the IDD sequences?"

Fatigue's written all over her. "Is it a spacecraft safety issue?" she asks.

No, it's not. And our SOWG chair doesn't feel like bitching about it, either. We don't fix it.

So today just was not a good day. It doesn't help when, during our end-of-day post-mortem, our other TUL, Matt Keuneke, says that they discovered that a heading of 80 degrees actually would have been okay after all. We didn't need to switch to the 120-degree heading, with all the problems that introduced. "I didn't feel like we should tell you, though," he says. "I figured you'd kill me."

I'm too tired to care about it. I think that's a real bad sign.

[Next post: sol 753, February 14.]

The science team has identified four rocks in the vicinity that they'd like us to drive to -- A, B, C, and D. Rocks C and D are definitely out; they'll take multiple sols to get to, and one constraint on the solution is that we strongly prefer something we can get to in one sol. Rocks A and B are about equally easy (or difficult) to get to, but A has a patch of sandy material around it, which B doesn't. So at yesterday's pre-plan meeting, I tentatively identified Rock B as the best candidate.

Last night, I took a more careful look, and started falling out of love with that idea. Another constraint on our solution is that we want to be able to RAT-brush our chosen rock, so that we can get a clean APXS measurement on it, and the RATtable face of Rock B is aimed somewhat away from the best path to it. To get to that face, we'd have to clamber up onto the rock pile beside it, which would simultaneously raise our tilt and reduce the stability of our footing. So that's bad all around.

I send out email about that, and the science team weighs the options at the SOWG meeting. What it comes down to is that Rock A is more eroded, so that there will be less layering for the MI. While Rock B offers better MI-ability, the uncertainty about being able to RAT it tilts the choice in the other direction. So Rock A it is.

Before we drive there, we've got some IDD work to finish up at our present location. And it looks like it's going to be hairy; the scientists are still dithering about exactly what they want, and that never turns out well. I turn to Paolo, RP-2 today and still in training to be a full rover driver. "Paolo, which one do you want?" I ask him. "The drive or the IDD?"

"I'm more comfortable with the drive," he says.

"Great!" I answer. "You get the IDD!"

"I knew that was going to happen," he laughs.

Today's going to be tough for him, I can see that. But at some point he's going to have to get his trial by fire, and it might as well be today.

So Paolo and Terry (who's shadowing him) work on the IDD sequence while I put the drive together. The drive to Rock A turns out to be not so terribly complex; we're basically just backing downhill past it, turning, and crawling back up a bit to put it right in the IDD work volume. As always, the devil's in the details, but all in all it goes quite well.

That is, until the TUL tells me there's another constraint on the drive. We've got to be at a heading of 120 degrees for comm. This is significantly different from the "natural" heading we'd otherwise end up at, about 80. It requires a completely different approach, and that means I've got to scrap almost all the work I've done -- I had already finished -- and start over.

A false start or two later, and I've got the new approach roughed out. We'll back somewhat farther downhill, curving until we're straight downslope from Rock A, then turn to about 120 degrees and climb back up to it. This is going to suck. It'll take longer, it means we're trying to drive up a steep slope through sandy material (with the attendant risk of getting bogged down and possibly even picking up a potato), and we've got less time to study it now.

We don't even notice until the walkthrough that the new approach leaves us with the left front wheel up on a 16cm rock. And there's just not much we can do about it, either. As Paolo points out, our choice of destination constrains us in X and Y, and our heading is dictated to us by comm. Therefore, the rover's final position and orientation are more or less completely determined by the constraints on the solution, and if there's a rock under the wheel as a result, then there's a rock under the wheel. We're able to shift the rover's position by a few cm, but will it be enough? Doubtful.

All in all, I'm quite frustrated by this outcome. We were trying so hard to find a scientifically desirable rock we could reach in one sol; our sols here are already limited, and Monday we enter restricted sols, which means we'll blow two more sols if this doesn't work. And I don't have any confidence that it will work: I think we'll come in Monday and have to reposition. This just sucks.

Worse yet, switching to Rock B (or C or D) at this point wouldn't help: C and D are more than one sol away no matter what we do, and B still has the same problem of higher tilt plus unsure footing, especially if we know we'll have to come at it with a 120-degree heading. So we wouldn't have options to fall back on even if the team weren't too tired and stressed out to attack them.

With all this going on, it's no wonder we discover -- after delivering -- an error in Paolo's IDD sequence. One part of the sequence is a column of MI stacks marching up the rock face. The rock face curves away from us slightly, and Paolo's sequence doesn't account for that. As a result, we're not quite touching the rock at the top end of the mosaic, and the resulting MI images might be out of focus (though the lower images in the stack will probably be just fine). Maybe I shouldn't bother with this, but I have to do my job. I smile sweetly at our TUL.

"Hey, Colette," I say as casually as I can. "What would you say if I told you there was a problem in the IDD sequences?"

Fatigue's written all over her. "Is it a spacecraft safety issue?" she asks.

No, it's not. And our SOWG chair doesn't feel like bitching about it, either. We don't fix it.

So today just was not a good day. It doesn't help when, during our end-of-day post-mortem, our other TUL, Matt Keuneke, says that they discovered that a heading of 80 degrees actually would have been okay after all. We didn't need to switch to the 120-degree heading, with all the problems that introduced. "I didn't feel like we should tell you, though," he says. "I figured you'd kill me."

I'm too tired to care about it. I think that's a real bad sign.

[Next post: sol 753, February 14.]

2011-02-10

Spirit Sol 749

I'm on Spirit today, and Spirit doesn't start planning until 13:00. But I don't get to sleep in: since I'm also an Opportunity driver, I have to come in early for a meeting about Opportunity's drive strategy and the latest on the stow/unstow business.

It sounds to me as if the Opportunity science team hasn't yet grasped the consequences of our situation, or isn't that gung-ho about getting south to Victoria, or some of each. Squyres wants to "turn the keys over to the rover planners," as he's put it, and let us book to Victoria as fast as possible. I'm sure that at least part of what's behind this is to try to get us to that crater, the so-called geological promised land, while we still have a working IDD.

But the near-term consequence of this choice would be that we'd likely bypass Payson, a juicy chunk of outcrop in a corner of Erebus Crater. And the rest of the Opportunity science team doesn't want to give that up. Instead, they want us to descend into Erebus Crater, wade through tens of meters of sandy stuff to get to a point from which we can image Payson, then struggle on further to a point from which we can exit Erebus, maybe. Unless we can't exit there, and need to go all the way back to where we started. All this we're supposed to do with an IDD that we have to guarantee we can safely unstow at the end of each drive as we plow through that stuff.

But the science team obviously feels strongly about this. Jim Erickson ducks in to say that there's a rebellion brewing -- the science team against Steve. "We need an answer for them," he says. "Give them time to go berserk, argue, and come to a decision."

We've got a story already: go about 80m south, evaluate the path into the crater, and make a decision there. That'll have to do.

With this and other things, I miss the Spirit SOWG meeting for the first time since I don't know when. (As RP-2, I don't really have to be there, but I don't like to miss them anyway.) But thisol's not complicated, just a tool change. I leave it to Paolo and Ashley to put that together; it's simple and only takes a few minutes. When they show it to me, I ask idly, "So we're not hitting the turret limit or anything, right?"

Paolo brings up the plot of the turret angles, and it shows we're going to 3.15. "Ah, shoot," I say. "Our limit is 3.14."

So they have to do it the hard way, tweaking the target's surface normal and redoing the approach. This takes at least half an hour of tedious work, and Paolo's barely able finish it before he has to rush off to do something else. But he gets it done, and it looks great. We're now going only to about 3.09, well away from the 3.14 value.

In the few minutes remaining before the walkthrough, I sit down to check out the details myself, including running our flight rule checker on it. Among other things, the flight rule checker knows the acceptable turret limits -- which, it turns out, I've misremembered. The upper limit is 3.3. We were fine in the first place. I made Paolo and Ashley do all that work for nothing.

I put the sequence back the way it was, walk through it in that state, and deliver. When Paolo returns, I apologize profusely, but he good-naturedly laughs it off. "It was good experience," he points out. There are sols when we really need to do that, and, as he says, he needed the practice.

Still. I am such an idiot.

Courtesy Wikipedia. Erebus Crater, looking from a distance at the Payson outcrop that was so attractive to the science team.

It sounds to me as if the Opportunity science team hasn't yet grasped the consequences of our situation, or isn't that gung-ho about getting south to Victoria, or some of each. Squyres wants to "turn the keys over to the rover planners," as he's put it, and let us book to Victoria as fast as possible. I'm sure that at least part of what's behind this is to try to get us to that crater, the so-called geological promised land, while we still have a working IDD.

But the near-term consequence of this choice would be that we'd likely bypass Payson, a juicy chunk of outcrop in a corner of Erebus Crater. And the rest of the Opportunity science team doesn't want to give that up. Instead, they want us to descend into Erebus Crater, wade through tens of meters of sandy stuff to get to a point from which we can image Payson, then struggle on further to a point from which we can exit Erebus, maybe. Unless we can't exit there, and need to go all the way back to where we started. All this we're supposed to do with an IDD that we have to guarantee we can safely unstow at the end of each drive as we plow through that stuff.

But the science team obviously feels strongly about this. Jim Erickson ducks in to say that there's a rebellion brewing -- the science team against Steve. "We need an answer for them," he says. "Give them time to go berserk, argue, and come to a decision."

We've got a story already: go about 80m south, evaluate the path into the crater, and make a decision there. That'll have to do.

With this and other things, I miss the Spirit SOWG meeting for the first time since I don't know when. (As RP-2, I don't really have to be there, but I don't like to miss them anyway.) But thisol's not complicated, just a tool change. I leave it to Paolo and Ashley to put that together; it's simple and only takes a few minutes. When they show it to me, I ask idly, "So we're not hitting the turret limit or anything, right?"

Paolo brings up the plot of the turret angles, and it shows we're going to 3.15. "Ah, shoot," I say. "Our limit is 3.14."

So they have to do it the hard way, tweaking the target's surface normal and redoing the approach. This takes at least half an hour of tedious work, and Paolo's barely able finish it before he has to rush off to do something else. But he gets it done, and it looks great. We're now going only to about 3.09, well away from the 3.14 value.

In the few minutes remaining before the walkthrough, I sit down to check out the details myself, including running our flight rule checker on it. Among other things, the flight rule checker knows the acceptable turret limits -- which, it turns out, I've misremembered. The upper limit is 3.3. We were fine in the first place. I made Paolo and Ashley do all that work for nothing.

I put the sequence back the way it was, walk through it in that state, and deliver. When Paolo returns, I apologize profusely, but he good-naturedly laughs it off. "It was good experience," he points out. There are sols when we really need to do that, and, as he says, he needed the practice.

Still. I am such an idiot.

Courtesy Wikipedia. Erebus Crater, looking from a distance at the Payson outcrop that was so attractive to the science team.

2011-02-07

Spirit Sol 746

We're not starting until 11:00, but I'm in at 09:00, and it turns out John has been here a while already. "Need any help working out the drive?" I ask him.

"Drive's already done," he shrugs.

Which is reasonably close to the truth. All the drive-related data came down yesterday, so we've already got enough to plan, and John's roughed out the approach already. He's got us climbing up the side of Home Plate to a patch of coarse-grained outcrop the scientists are slavering over. When we get up there, our pitch is going to be over 20 degrees. Hillary, all over again.

OK. When we were at Hillary, what did we wish we'd had? Wiggle-cams, for one thing. Higher-precision data at the end of the drive, for another. So we include that stuff in this sequence.

Speaking of drives, the Opportunity drive Frank and I planned Friday crapped out: we backed up a meter, turned, and tripped the hyper-ultra-paranoid suspension limits during the turn. So we're not where we wanted to be. What makes this more painful is that we knew the bogies had hit 5.5deg coming in here, and the limits we've been using were 6deg -- so we knew this might happen, discussed it, and decided not to mess with the limits. Now I kind of wish we had (though Ashitey points out that maybe it's better we didn't: we're supposed to be conservative like this while we get used to this new hover-stow driving).

Having screwed up both Spirit and Opportunity drives in the last week or so, it's hard not to feel like I'm in something of a slump. I hope that tomorrow's data shows I'm out of it.

[Next post: sol 749, February 10.]

"Drive's already done," he shrugs.

Which is reasonably close to the truth. All the drive-related data came down yesterday, so we've already got enough to plan, and John's roughed out the approach already. He's got us climbing up the side of Home Plate to a patch of coarse-grained outcrop the scientists are slavering over. When we get up there, our pitch is going to be over 20 degrees. Hillary, all over again.

OK. When we were at Hillary, what did we wish we'd had? Wiggle-cams, for one thing. Higher-precision data at the end of the drive, for another. So we include that stuff in this sequence.

Speaking of drives, the Opportunity drive Frank and I planned Friday crapped out: we backed up a meter, turned, and tripped the hyper-ultra-paranoid suspension limits during the turn. So we're not where we wanted to be. What makes this more painful is that we knew the bogies had hit 5.5deg coming in here, and the limits we've been using were 6deg -- so we knew this might happen, discussed it, and decided not to mess with the limits. Now I kind of wish we had (though Ashitey points out that maybe it's better we didn't: we're supposed to be conservative like this while we get used to this new hover-stow driving).

Having screwed up both Spirit and Opportunity drives in the last week or so, it's hard not to feel like I'm in something of a slump. I hope that tomorrow's data shows I'm out of it.

[Next post: sol 749, February 10.]

2011-02-04

Opportunity Sol 723 (Spirit Sol 743)

Yestersol I came in with Matt Heverly and Frank Hartman to take a look at the RP-0 sequences Jeng and Ashitey had put together for thisol. To our astonishment, they'd decided to send up the previous sol's sequences despite wrist-flip problems -- which can cause the sequence to fault out, if you're even a little unlucky -- and their RP-0 sequences had the same problem. Yestersol's sequences worked fine, but Frank and I are of one mind that thisol's need to be fixed.

However, despite our needing to make some small changes to both the IDD and drive sequences, the draft versions save us a lot of time and stress. More than enough for me to start putting together canned stow, unstow, and rotor-resistance-setting sequences for us to use in our new stow/drive/unstow driving routine. (To my annoyance, we decide not to uplink these sequences on this sol, because we haven't yet figured out how we're going to safely deactivate them if they should run unusually long. But I get them built, anyway.)

Martian winter is setting in. One of our first signs of it is longer heating times required in the drive sequences, after which we tell the spacecraft to expect colder temperatures despite the heating. And, Bill Nelson points out, we're no longer in a relatively warm crater, as we were last winter; we're out on the chillier plains. This is bad news for Opportunity's Mini-TES, which is especially vulnerable to the extra-cold temperatures it experiences when we must Deep Sleep to conserve power. They call Squyres to ask him about this -- should we curtail activities to avoid Deep Sleeping, or accept the additional risk? "Take the risk," is his call. You can hear the shrug. "We made this decision basically one Martian year ago." If we lose the MTES, we lose it -- although that would truly suck on a rover that already has a failing IDD. If the IDD and the MTES both go, we're left with only the PCAM for science instruments.

The power loss has another implication: we'll have to Deep Sleep nightly, meaning we'll have fewer comm passes, meaning we'll get less data daily. (If we won't have any science instruments to return data from, that's not so bad. I didn't just say that.) Frank's been asked to put together a scheme for driving with only 40 Mbits of downlink per sol, which I would have thought unlikely until he shows me the scheme. It'll be tight, but I think we can do it -- and oddly enough, I think this will help focus us on driving. We'll get to a point where we can't afford to do anything else.

Speaking of driving, John Callas stops in to pick my brain about strategies for driving more meters per sol on the way to Victoria, which NASA HQ is now apparently starting to push hard for. I talk about the same stuff with him as I have with Frank -- using autonav, lengthening the distance between slip checks, and so on.

But the big thing, I tell him, is to get the scientists pushing for driving. And the only demonstrated way to do that is with a drive metric: pick a sol, and say we're going to be there by that sol, and keep putting our progress (or lack of it) up on the board every day for all to see. This doesn't work perfectly; the scientists will spend on credit. And sometimes, as with Spirit, there isn't enough margin left, and we don't get to Home Plate on time. Not that I'm bitter. But it works well enough, all the same.

The odd part of this conversation comes when John reveals that he's a bit of a train nut. "Oh, if my dad ever comes out for a visit, I'll have to introduce you," I tell him. "He was an engineer for CSX transportation -- retired just a year or so ago."

John's eyes light up like a little kid's. "When is your dad coming for a visit?" he asks eagerly.

A visit from one project manager just wouldn't be enough. Our sadly-soon-to-be-ex-project manager, Jim Erickson, also pops by. He's already splitting his time, and soon he'll be gone from MER for good. Julie asks him how things are going.

"Okay," he says.

"Just okay?"

He shrugs. "It's much less fun to do two things badly than to do one thing well," he says.

[Next post: sol 746, February 7.]

However, despite our needing to make some small changes to both the IDD and drive sequences, the draft versions save us a lot of time and stress. More than enough for me to start putting together canned stow, unstow, and rotor-resistance-setting sequences for us to use in our new stow/drive/unstow driving routine. (To my annoyance, we decide not to uplink these sequences on this sol, because we haven't yet figured out how we're going to safely deactivate them if they should run unusually long. But I get them built, anyway.)

Martian winter is setting in. One of our first signs of it is longer heating times required in the drive sequences, after which we tell the spacecraft to expect colder temperatures despite the heating. And, Bill Nelson points out, we're no longer in a relatively warm crater, as we were last winter; we're out on the chillier plains. This is bad news for Opportunity's Mini-TES, which is especially vulnerable to the extra-cold temperatures it experiences when we must Deep Sleep to conserve power. They call Squyres to ask him about this -- should we curtail activities to avoid Deep Sleeping, or accept the additional risk? "Take the risk," is his call. You can hear the shrug. "We made this decision basically one Martian year ago." If we lose the MTES, we lose it -- although that would truly suck on a rover that already has a failing IDD. If the IDD and the MTES both go, we're left with only the PCAM for science instruments.

The power loss has another implication: we'll have to Deep Sleep nightly, meaning we'll have fewer comm passes, meaning we'll get less data daily. (If we won't have any science instruments to return data from, that's not so bad. I didn't just say that.) Frank's been asked to put together a scheme for driving with only 40 Mbits of downlink per sol, which I would have thought unlikely until he shows me the scheme. It'll be tight, but I think we can do it -- and oddly enough, I think this will help focus us on driving. We'll get to a point where we can't afford to do anything else.

Speaking of driving, John Callas stops in to pick my brain about strategies for driving more meters per sol on the way to Victoria, which NASA HQ is now apparently starting to push hard for. I talk about the same stuff with him as I have with Frank -- using autonav, lengthening the distance between slip checks, and so on.

But the big thing, I tell him, is to get the scientists pushing for driving. And the only demonstrated way to do that is with a drive metric: pick a sol, and say we're going to be there by that sol, and keep putting our progress (or lack of it) up on the board every day for all to see. This doesn't work perfectly; the scientists will spend on credit. And sometimes, as with Spirit, there isn't enough margin left, and we don't get to Home Plate on time. Not that I'm bitter. But it works well enough, all the same.

The odd part of this conversation comes when John reveals that he's a bit of a train nut. "Oh, if my dad ever comes out for a visit, I'll have to introduce you," I tell him. "He was an engineer for CSX transportation -- retired just a year or so ago."

John's eyes light up like a little kid's. "When is your dad coming for a visit?" he asks eagerly.

A visit from one project manager just wouldn't be enough. Our sadly-soon-to-be-ex-project manager, Jim Erickson, also pops by. He's already splitting his time, and soon he'll be gone from MER for good. Julie asks him how things are going.

"Okay," he says.

"Just okay?"

He shrugs. "It's much less fun to do two things badly than to do one thing well," he says.

[Next post: sol 746, February 7.]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)